Select on RRR bitvector

Currently, I am working with Rayan Chikhi and two students on a library for bioinformatics that uses a bitvector to store information and rank and select operations to interrogate it.

As our bitvector can be composed of $4^{64}$ bits, we have to represent in a compacted or compressed way.

During my readings on bitvectors I found the papers of Raman, Raman and Rao (that's why RRR) in [SIM-SIAM symposium in 2002](https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/545381.545411) and [ACM Transactions on Algorithms in 2007](https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1290672.1290680).

This is not the bitvector that we are currently using but the technics for performing rank and select in constant time are very interesting.

The details of the datastructure are very hard to understand and thankfully to Alex Bow, the rank operation datastructure have been explained in a [previous blogpost](https://alexbowe.com/rrr/).

Here I will try to be as clear as possible to describe the datastructure supporting the select operation in constant time.

# Rank and Select

First let's describe the rank and select operations on a bitvector $b$ of size $m$ where $b_i$ is the $i^{th}$ bit of the vector.

The operations are described as follow:

* $rank_{1}(i) = \sum_{j=0}^{i}{b_j}$ : Count the number of 1 from the beginning of the vector to the ith position.

* $rank_{0}(i) = i - rank_{1}(i)$ : Count the number of 0 from the beginning of the vector to the ith position.

* $select_{u}(i) = min(x \| rank_{u}(x) == i)$ : Return the position of the ith bit set to $u$.

For this post, I will assume that there is a majority of 0 in the bitvector and that we want to perform rank and select operations on bits set to 1.

Of course, everything is symmetrical, so it's easy to replace the 1s by 0s.

# Bitvector structure

A bitvector has two main parameters: its size and the number of bit set to 1.

I will call $m$ the size of the bitvector and $n$ the number of 1.

By definition, a fully explicit bitvector occupy $m$ bits into memory.

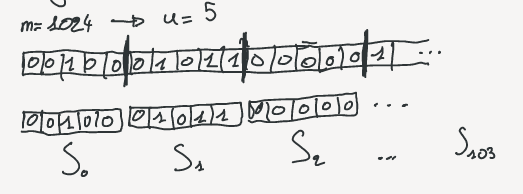

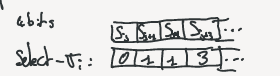

The RRR bitvector is sliced into small blocks of equal size $u$ (For optimality in the article $u = { {1}\over{2} } lg\,m$).

Each block represent a chunk of the bitvector that we call $S_i$ and there are $p$ blocks ($p = m / u$).

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

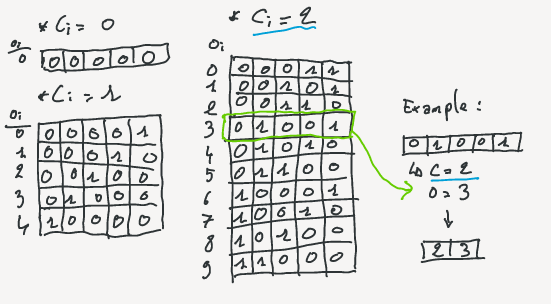

Each of the $S_i$ can be represented by two integers: the number of bit set to 1 $c_i$ and an offset identifier ($o_i$).

The number of bit set is also called *class* of the chunk.

The are exactly ${u\choose c_i}$ different possible blocks containing $c_i$ bit set to 1.

Imagine that all these possible blocks are sorted lexicographically, then $o_i$ is the position of the block in that order.

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

For each block, storing $c_i$ take exactly $\lceil lg\,u \rceil$ bits regardless the block.

Storing $o_i$ take $\lceil lg{b\choose c_i} \rceil$ bits.

So, the amount of bit needed for a basic block depend on its class.

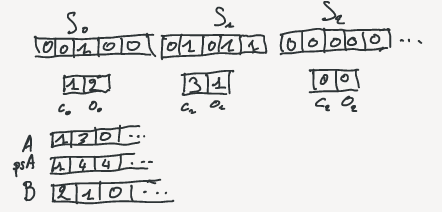

The values are computed in two different arrays: A for classes and B for offsets.

A prefix sum array is also computed on A where $psA[i] = \sum_{j=0}^{i-1}{A[j]}$.

Note that $psA[i] = rank(i \times u)$, so it will be use for fast access to rank values.

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

# Construction of the select datastructures

For rapid select operations some of the values are precomputed and used as anchors for the search.

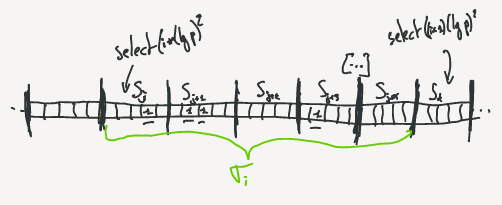

Instead of having select precomputed on regular indexes all along the vector, the RRR datastructure compute regular select values.

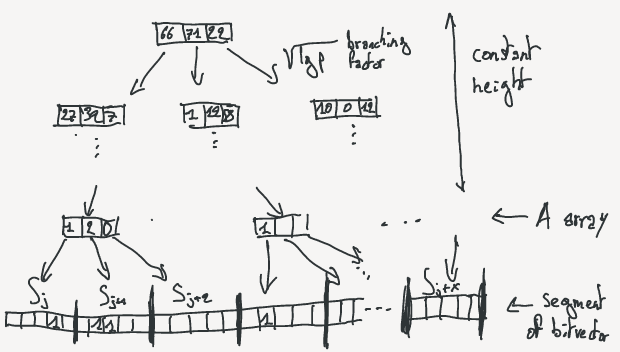

Regular select values means an array C where:

* $C[0] = 0$

* $C[i] = \lfloor {select(i \times c) \over u} \rfloor$, with $c = (lg\,p)^2$

By the division by u, we keep track of the block indices where the select remains.

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

We now define a segment of blocks $\sigma_i$ as a consecutive list of block starting at $C[i]$ and ending at $C[i+1]-1$.

$\sigma_i$ is called sparse if it contains at least $(lg\,p)^4$ bits, dense otherwise.

In sparse segments, the block index of the select are explicitly stored.

To save space, the block indexes are relative to the beginning of the segment.

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

For dense segments, a tree datastructure is created with a branching factor of $\sqrt{lg\,p}$.

So, because there is at most $(lg\,p)^4$ bits, the height of the tree is bounded by a constant.

The leaves of the tree are the blocks of the segment.

The nodes are arrays containing the numbers of bit set to 1 in the subtrees.

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

# (Almost ?) O(1) select requests

Figure globale select

Let's consider that we want to perform a request select(x), where $0 <= x <= m$

1. First, find the block segment where the select belongs to.

By computing $i= \lfloor x / \lfloor (lg\,p)^2 \rfloor \rfloor$, we know that the select value should be part of $\sigma_i$ or the beginning of the next block.\\

\\

{:refdef: style="text-align: center;"}

{: refdef}

2. It is possible that the select value is contained in the following bloc of $\sigma_i$ before the index of $select((i+1)(lg\,p)^2)$.

So, we have to verify the beginning of the C[i+1] block (The green section on the above schema).

If $rank(C[i+1] \times u) > (i+1) \times (lg\,p)^2$ (ie. $psA[C[i+1]]$), the value is contained in $C[i+1]$

3. If the value is not part of C[i+1], we have to look inside of $\sigma_i$.

* If it's sparse, go to the beginning of the sparse segment datastructure. The relative indexes of the blocks containing the ones are explicitly stored. So, first get the relative select value by doing $r = x - rank(C[i])$. Then get the relative index for the block of interest with $j_{rel} = \sigma_i[r]$. Finally the absolute index of the bloc is obtained by doing $j_{abs} = C[i] + j_{rel}$. The selected bit is inside of the block of index $j_{abs}$.

* If it's dense, go to the root of the tree for $\sigma_i$.

As for the sparce block, we are looking for a relative index $j_{rel}$ from the beginning of the segment.

If the current node of the tree is n, n[x] is the $x^{th}$ cell of the array in the node.

Search for the cell i such as $n[i] \leq j_{rel} < n[i+1]$.

This search is easily done in log time as the nodes are partial sum arrays.

The following node discuss about a constant time search.

Go to the corresponding subnode and recursively do the search until you reach a leaf.

The leaf is the block of interest.\\

\\

**Note**: As I just described, the search into a node partial sum array is performed in log time.

This leads to a non constant query time.

In the RRR article the authors claim "This can be done in constant time using a lookup table".

Thay also say that the whole structure can be stored in $O(\sqrt{lg\,p}\,lg\,lg\,p)$ but without further explanations.

In my mind, the only way to do it in constant time is to explicitely create one cell per possible select value at each level of the tree.

Because a segment is created with $(lg\,p)^2$ bit set to 1, the arrays are of size $(lg\,p)^2$.

This is not the same amount of memory than in the paper.

So, if you, the reader, are able to explain how to constant time query in this space, please contact me !

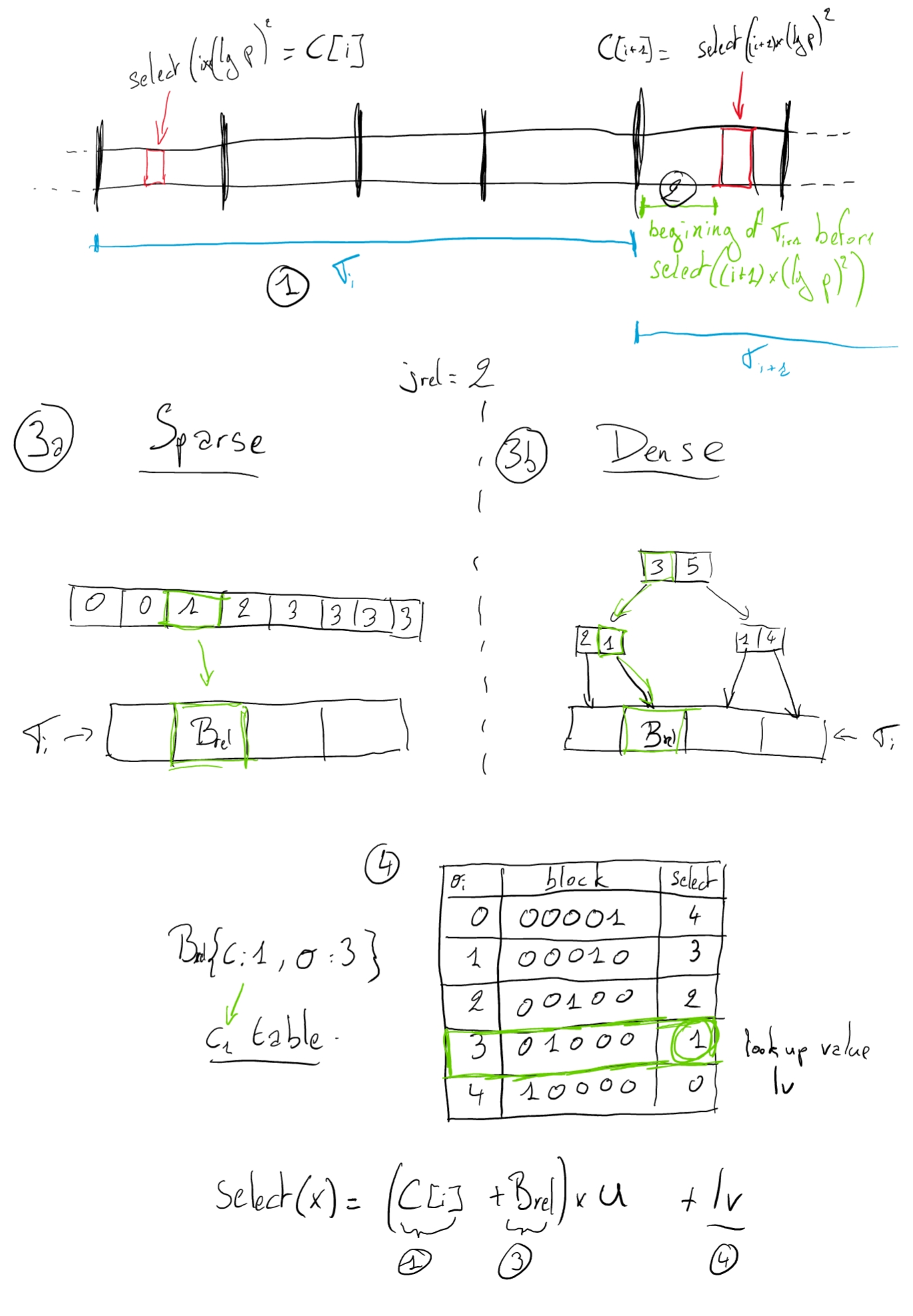

4. We have a block B from the step 3. We have to extract the relative value to the beginning of the block.

Here, everything is precomputed in a huge lookup table.

With the class and the offset of the block, we can directly jump to the precomputed row and then to the column corresponding to the selected bit inside of the block.

Finally, the select value is the sum of position of the selected segment, the relative index of the block inside of the segment and the relative position of the bit inside of the block.

# Remarks

This blogpost is only due to my curiosity on the theory but I think that this structure is not practical. Many improvements have be done since the first publication of this work. The purpose of the blogpost is only the clarification of the technics as the scientific papers about RRR are very complicated to read.

To understand and write this post, I was helped by Rayan Chikhi. I thank him a lot for the time that he used for it.